26 Sep Design under pressure

An important new DIA discussion paper reveals that while Australian designers still love their job with a passion, times are getting tougher.

Each year it gets more difficult to attract new clients, average design income is going down, Australian manufacturing continues to shrink, and the influx of graduates and self-appointed ‘designers’ continues to rise.

Things are definitely not what they used to be.

The challenges of change

Despite individual foibles, designers are a microcosm of general society and share many, if not all, of the aspirations, joys and fears of our fellow citizens.

As a recognised group within the creative professions, designers are often at the forefront of change: indeed, it could be argued that it is their professional duty to encourage and embrace change for themselves and for their clients.

But change is a two-edged sword: rarely controllable, it deals and withdraws favours according to its own imperious agenda, ignoring our own.

With the advent of globalism, market inequalities, the acceleration of technologies, a boom in job seekers, the rise of out-sourcing and crowd-sourcing, and the blurring of boundaries between what is and isn’t design and who is best qualified to deliver it, designers today are facing unprecedented challenges.

Problems and opportunities

It is also arguable that the same conditions are producing unrivalled opportunities for those designers able and willing to adapt to the new global market paradigms – but that will depend on a designer’s skill set and whether they reside in the ‘glass half full’ or ‘glass half empty’ camp.

As Australia’s peak professional body representing many disciplines of qualified, professional designers, the Design Institute of Australia is uniquely positioned to identify and analyse current design industry trends and issues.

The DIA surveys industry conditions in conjunction with its long-running Fees and Salary Surveys, and as part of those surveys, a discussion paper entitled ‘Australian Design 2013’ – based on the responses of design businesses, individuals and design academics in 2003 and 2011/12 – has recently been released.

Critical information

The discussion paper draws conclusions that have profound implications for current and future professional Australian designers and design businesses, and was carried out for the DIA by David Robertson LFDIA, industrial and graphic designer, business owner, and highly respected multiple-term DIA National President (2000-2008).

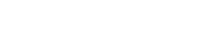

With the 2003 survey acting as a benchmark for the 2011 survey, designers were invited to comment on what they considered to be the important issues facing them and what actions they would like taken to address those issues.

According to David Robertson, the DIA survey and associated discussion paper are important because of the number of Australian designers surveyed, the unbiased nature of their responses and the credibility of the organisation conducting the survey – the DIA.

Issues and actions

‘The DIA Fees and Salary Surveys provide a unique and informative snapshot of designers, design issues and of the profession itself as we head into the future,’ he said.

‘In addition to providing critical real world data about Australian designers’ incomes, the surveys also identified what professional designers in all categories perceived as being the major issues of concern to them.

‘Just as importantly, our surveys asked designers what actions they thought could be taken to address those issues.

‘The paper ‘Australian Design 2013’ is a discussion about the main issues identified by designers and what actions, if any, can or should be undertaken by the DIA or other bodies to address them.’

Factors of discontent

According to David Robertson, Australian designers responding to the surveys highlighted four major external factors affecting them over a long time frame:

- The education industry

- Technological change

- International trade changes

- Media and communication change.

‘All of these concerns expressed by the design community are real,’ explained Robertson.

‘The key question is which of them are capable of moderation by an organisation such as the DIA or any other body – and which of them represent desires that can never be met or are beyond the resources of a single professional group to alter?’

Oversupply

Robertson says that the four external factors identified in the survey are greatly affecting the employment outcomes for designers and design services in Australia.

‘It is absolutely clear that the total number of designers in Australia – both trained and self trained – far outstrips the realistic commercial demand for design services,’ says Robertson.

‘According to the 2011 Australian Census, there were in excess of 160,000 Australians with tertiary qualifications in aesthetic-based design disciplines.

‘This number includes architects, interior designers and decorators, industrial designers, graphic designers, web designers, textile designers, fashion designers, jewellery designers, and landscape and urban designers.’

Excessive competition

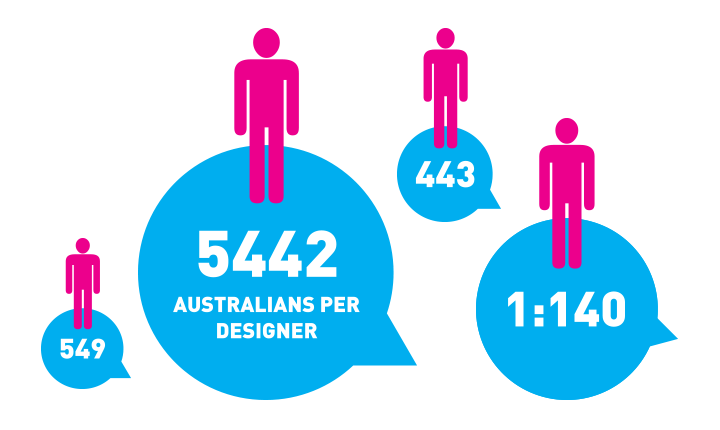

‘This means that 1 in every 140 Australians has design qualifications, or 0.71% of the population.

‘Of these 160,000 potential designers, around 89,000 had jobs in an ANZSCO-listed design occupation.

‘In many cases this job was a result of self-employment and more than one quarter of interior and graphic designers were in part time positions.

‘The Census does not reveal the many thousands operating at the periphery of the design industry while employed in some other occupation.

‘It should be no surprise therefore, that competition is the major issue for designers identified in our surveys.’

International access

According to Robertson, the level of competition in the design professions is multi-factorial, with educational trends and technology enabled skill transfer being just two of the driving forces contributing to an oversupply of designers and design services in Australia.

“It is absolutely clear that the total number of designers in Australia far outstrips the realistic commercial demand for design services.”

‘While digital communications make it possible for Australian designers to supply services internationally, the reverse is also true,’ says Robertson.

‘The natural concentration of design services with their symbiotic host industry means that the most nurturing environment for the service is close to the production location.

‘In the building and construction industry the supply of materials, furniture and custom fitments become increasingly easy to source internationally and harder to obtain from diminished sources of local production.’

‘In the area of graphic design, sections of the Australian customer base see no barrier or commercial detriment to using remote designers or internet enabled services such as crowdsourcing to provide marketing and sales materials.

‘Purchasers are becoming comfortable with digital transactions that include no face-to-face contact.’

Too many graduates

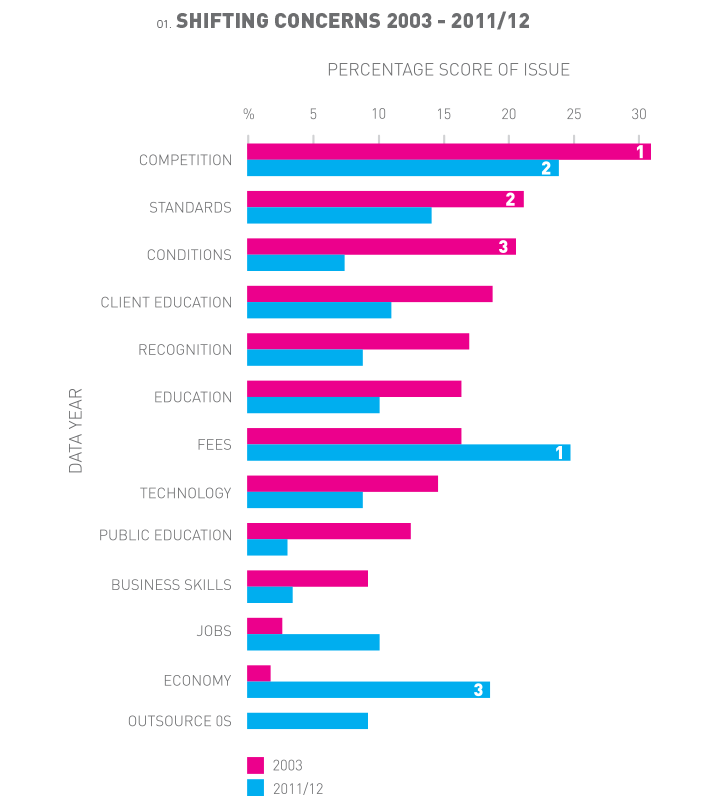

The proliferation of tertiary design education courses in Australia has also contributed substantially to the problem, says Robertson, with design employment opportunities lagging significantly behind the numbers of graduates.

‘Design (and in particular graphic design and interior design) has become a very visible study choice in comparison to the volume of jobs available,’ he claims.

‘There can be a belief that the existence of a tertiary course implies the existence of employment relating to it.

‘That is clearly not the case, but the design profession has no power to directly modify the numbers of graduates produced.

‘Only a clear message from the marketplace on job availability and remuneration levels will alter students’ decisions to purchase design education.’

Grass roots participation

The DIA survey identifies and discusses a number of other issues highlighted by designers, including skills atrophy, in-house design services, lack of skills recognition, maintenance and variability of education standards, demarcation, fee setting and descriptive occupational terms.

But as Robertson says, the point is not just that they exist but whether anything can be done to address them.

The possible remedial actions need to be a mix of individual and organisational effort, he says.

‘Designers cannot expect these efforts to all come from their professional associations,’ he asserts.

‘They must also provide significant personal action if they expect improvement in their working environment.’

Professional membership

‘Professional designers should increase their differentiation from other service providers by professional membership, accreditation, CPD, best practice consulting processes, and actively displaying their credentials,’ explains Robertson.

‘Becoming a member of a professional organisation like the DIA and actively supporting it is a crucial way of displaying your professional credibility and simultaneously giving a voice to your industry.’

For professional membership organisations like the DIA, Robertson says that the list of necessary actions is long and varied, but amongst them, a more objective, ‘warts and all’ assessment of the industry to secondary schools and parents of prospective design students to help avoid over-promotion of design and its job prospects is long overdue.

A united approach

‘Organisations like the DIA must and do lobby for greater awareness in government projects and procurement of the value of design as an economic magnifier,’ he says.

‘We also need to unite the DIA and other design support organisations to ensure that the design professions have a consolidated, well resourced organisational base capable of providing services to the design sector.’

It is not possible, he explains, to address every single issue raised by designers in the DIA survey, but many of those issues capable of being addressed already have strategies underway – with definite room for improvement in certain areas.

More information

This article presents only a portion of the results and issues identified in Australian Design 2013.

The full text of this important paper is available to all DIA members free of charge as DIA Practice Note PN034 (Issue B) 2013: ‘Australian Design 2013’. Visit the Practice Note section of www.design.org.au

01. The comparison between designers’ concerns in 2003 and 2011/12 aligned with the top key words from the surveys.

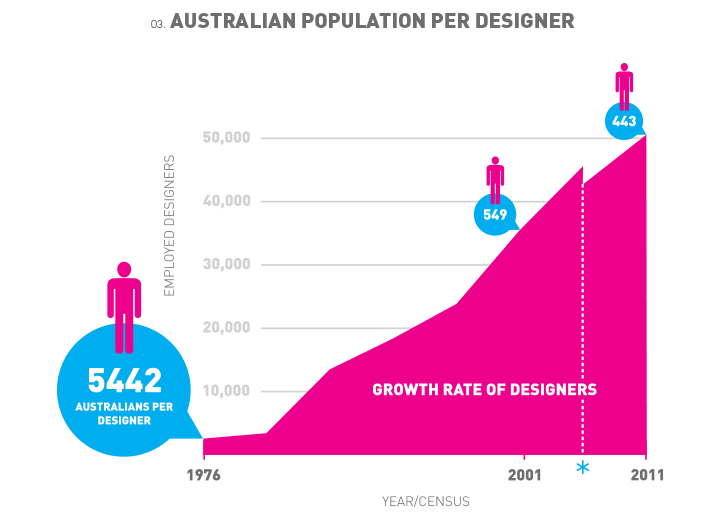

02. The progressive growth of design jobs aligned with available design graduates.

03. Each designer’s share of customers has shrunk in the last thirty five years. (architects not included in graph)

* The break in the graph shows the change to ANZSCO in 2006.

Published August 2013 | Spark